Ben Pitler

Human rights defender and University of Washington MBA candidate, data science/analytics track. Passionate about using data science to achieve justice.

This portfolio details my use of data science to investigate and document violations of international human rights law. Please direct all questions and requests to collaborate to ds4hrbp@protonmail.com

LinkedIn

The Egypt Death Penalty Index

The Egypt Death Penalty Index is a project from my time working for the British human rights organization Reprieve. Since the ascension to power of current President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi in early July 2013, Egyptian courts have handed down thousands of death sentences. With Reprieve, I investigated the cases of individuals facing unlawful execution in Egypt; I worked primarily on behalf of peaceful protestors and children sentenced to death in patently unfair trials.

In the course of working on individual cases, it became problematic that there did not exist anywhere in the world a single, codified database tracking all of those on Egypt’s death row. It was understandable why that resource didn’t exist–it would need to include detailed information about thousands of individuals, and building it would require considerable resources. That sounded like a challenge we could meet, so we set out to build it. With funding from the German Federal Foreign Office, I spent more than a year working with a team of researchers, lawyers, and human rights activists based in both London and Cairo. We fanned out across Egypt, collected and digitized paper court judgments, conducted interviews with victims and their family members, and built the world’s first comprehensive database tracking Egypt’s massive, unlawful application of the death penalty: the Egypt Death Penalty Index.

Data Collection and Verification

Collecting data for this project was complex. We documented death sentences through a combination of original court documents, media reports, contact with releveant lawyers, and information provided by leading Egyptian human rights organizations. We needed to balance comprehensiveness–we wanted to document every single death sentence–with accuracy. To achieve that, we made every effort to cross-verify all data points with at least two kinds of sources, and each row of data includes a column indicating which types of sources were used to verify it.

Data Organization and Analysis

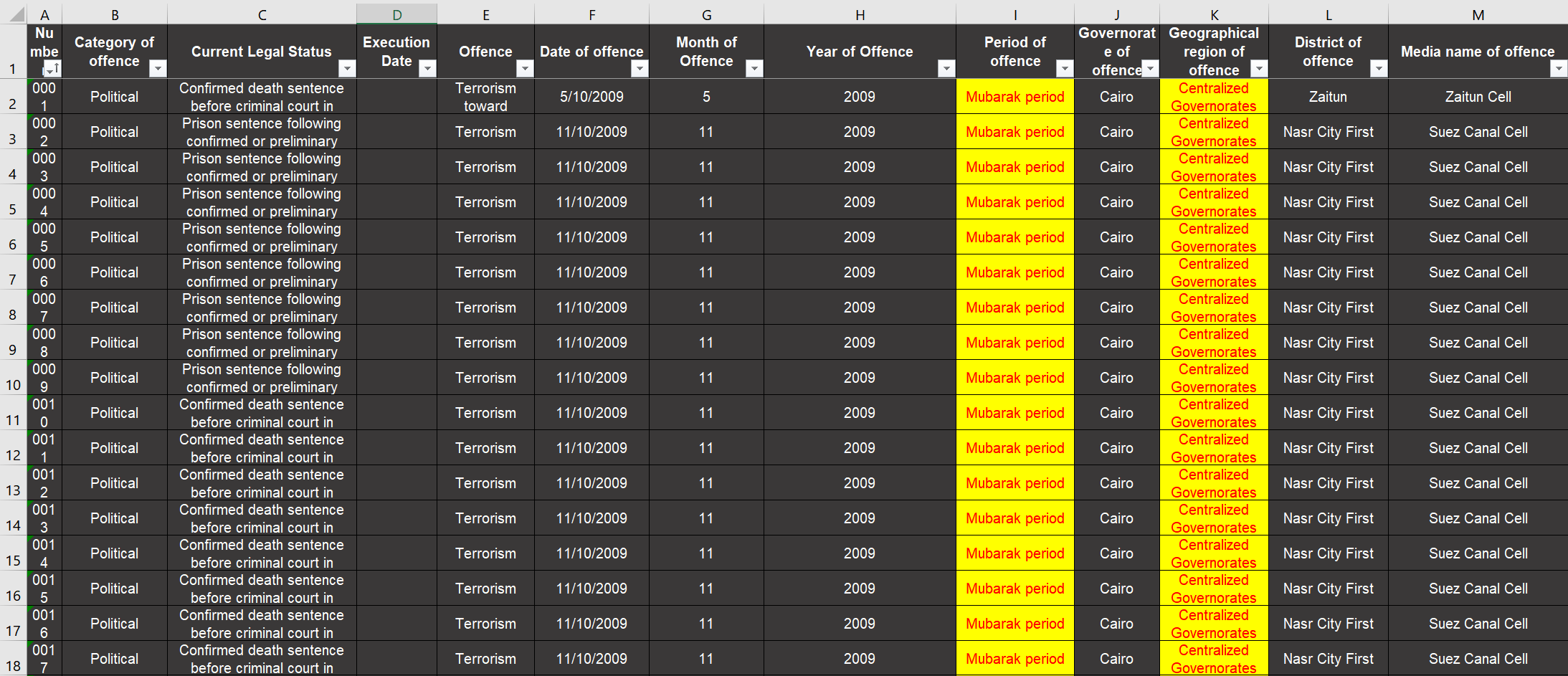

Initially this project existed entirely in the form of an Excel spreadsheet. When we first started working on the Index, I was quite proficient in using Excel to organize data and perform statistical analysis, but I was still a beginner in R and Python. As such, the dataset’s initial form was an Excel sheet that looked like this:

This was sufficient for the data’s first incarnation. Through pivot tables and relatively simple Excel functions, we were able to extract statistical observations about Egypt’s application of the death penalty. This included novel observations related to geographic distribution of death sentences, mass trials as tools of political repression, and the especially disturbing trend of children being sentenced to death in Egyptian courts.

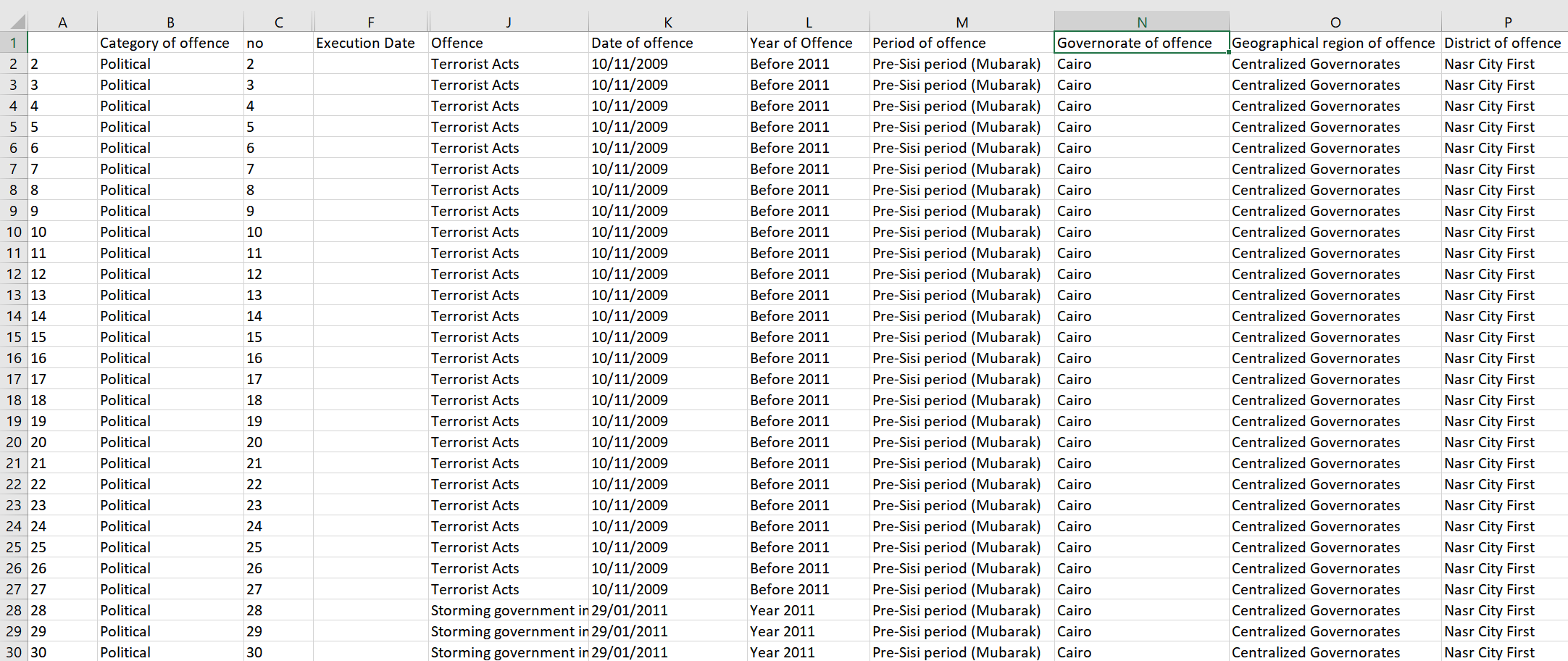

Later in the life of the project, the data was reformulated into a .csv file, which looks like this:

Now, R is used to extract insights from the dataset, and the project no longer depends on analysis taking place within Excel.

Website

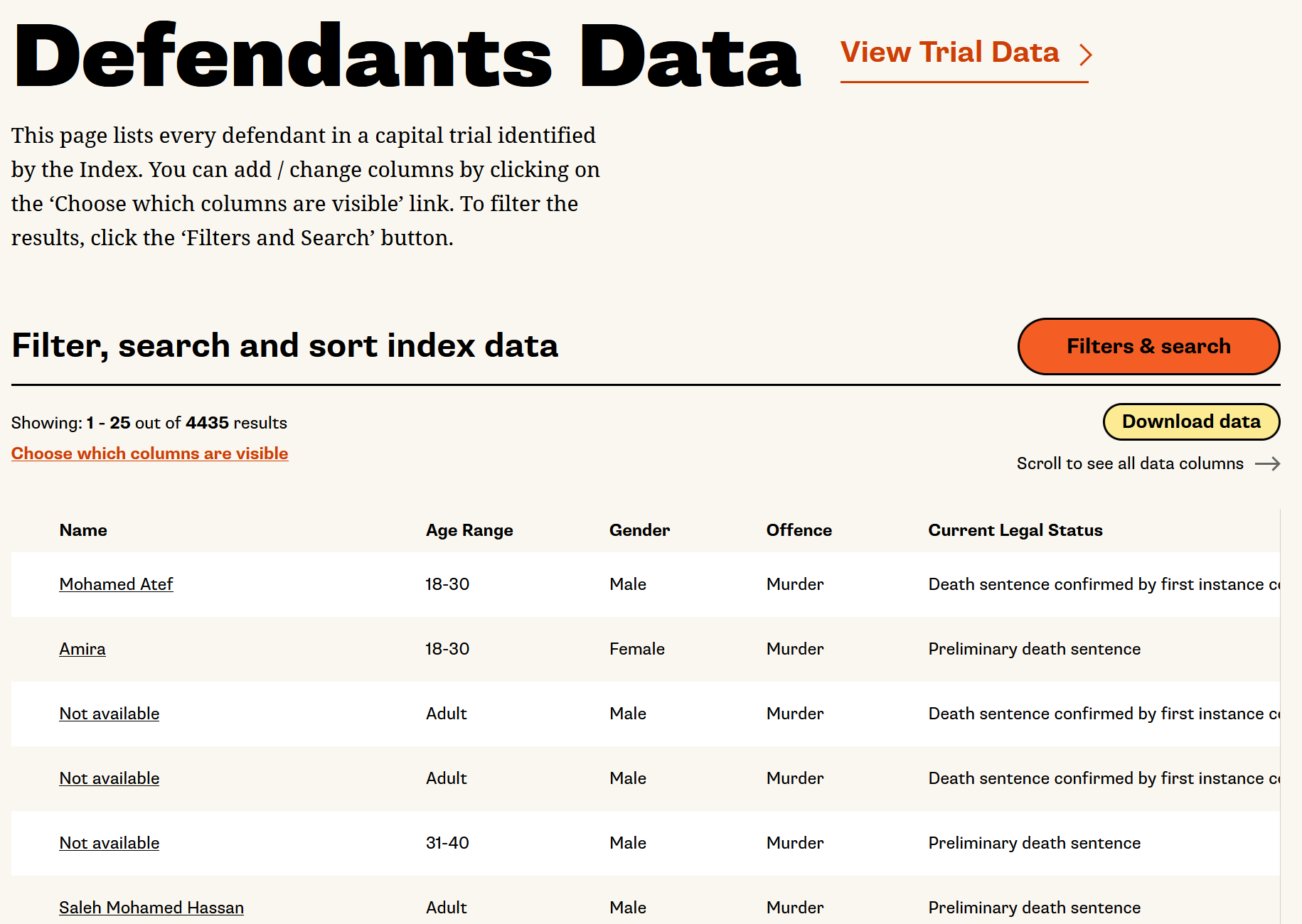

The idea behind the Index was not only to collect this data and build a dataset, but also to create an intuitive website that would allow human rights activists, journalists, policymakers, and the general public to interact with the data and understand key insights. The Egypt Death Penalty Index website reproduces the underlying dataset in an easily navigable web interface where users can view, search through, filter, and sort data regarding individual defendants in death penalty cases or capital trials that have led to death sentences:

The data is available to the public for download in its raw form, and users can also access digital copies of the original court documents we collected.

Insights

The concentration of this data in one location allowed us to pull out a number of hitherto unknown facts about Egypt’s application of the death penalty. Since 2011, Egypt has:

- Handed down preliminary death sentences to at least 17 children

- Handed down more than 2,300 preliminary death sentences overall

- Handed down 1,670 confirmed death sentences

- Executed 226 people

- Handed down 190 preliminary death sentences in military tribunals

Impact

This database is the first of its kind; little of this information was known before the creation of the Index. Everyone knew that the Egyptian government was sentencing shocking numbers of people to death, but the crisis was so large that it was impossible to say just how many people were affected. This project made that possible for the first time, and we saw immediate results in our advocacy. Prior to the creation of the Index, when we lobbied senior officials at the UN or the EU to intervene in death penalty cases, they would ask for data regarding Egypt’s overall application of the death penalty, and we couldn’t provide it. Once we created the Index, we were able to contextualize individual death penalty cases with hard numbers, making concrete the horrible reality of Egypt’s death penalty crisis.

This paid dividends. It made our advocacy more compelling and led to a number of policy wins for the organization. The biggest impact came in our work on the cases of juveniles sentenced to death. We had been telling policymakers and government officials for years that Egypt was sentencing children to death, while the Egyptian government denied the claim. The data emerging from the Index allowed us to show that Egypt had handed preliminary death sentences to more than two dozen children, despite the existence of both international and Egyptian law forbidding the practice. This helped us identify the specific legal loophole allowing this to take place, and make tangible progress in engineering international political pressure on Egypt to close it.

This project is a great example of the kind of data-forward work that is sorely needed in the human rights investigations field. Egypt’s repressive government, a serial violator of international human rights law, has a vested interest in ensuring that reliable data regarding its violations is not available to the public. There is no centralized government database regarding death sentences or executions; the government doesn’t even publish press releases about these issues. Where data that should be public and open is instead hidden by powerful interests, human rights defenders need to know how to find that data and bring it to light.